Labs are undertaken by teams of 2 - 6 people, to work collectively to build a project or accomplish a task.

Registration: Sign up individually or register a team.

Spring Project

The Spring Project is to build a Co-Machine using scavenged materials.

A Co-Machine is a machine that subverts, disrupts, or asserts public space. It imagines "possible alternatives for inhabiting our city" (Dan Dorocic) while challenging gentrification, asserting the rights of a community, or sustaining an alternative existence.

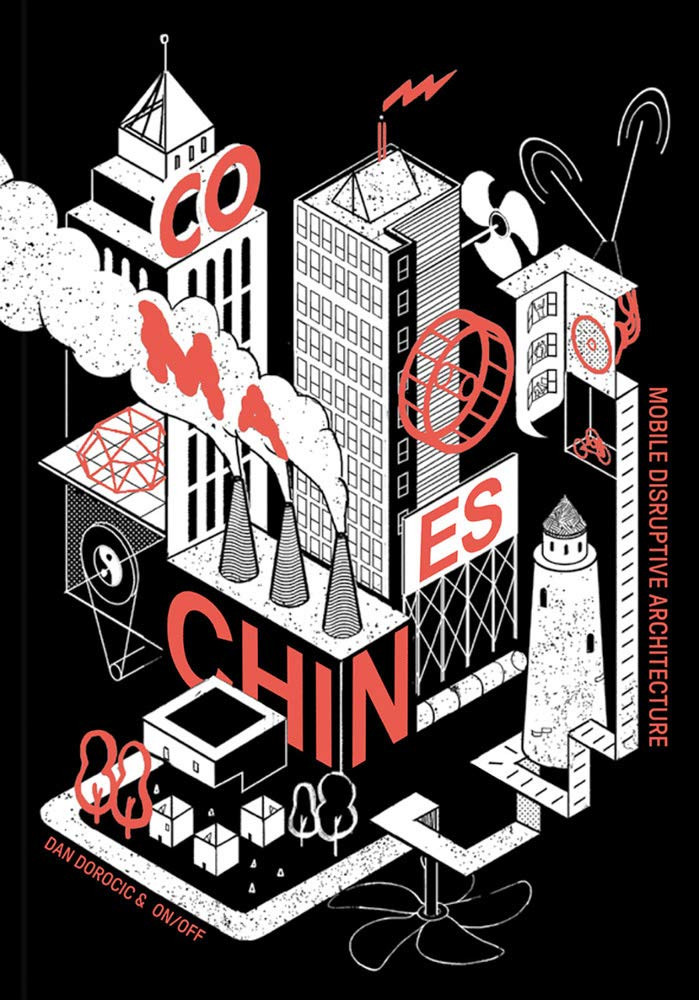

This project was inspired by the book Co-Machines: Mobile Disruptive Architecture, published by Onomatopee Projects, edited by Dan Dorocic and the design studio, On-Off.

Materials: Machines must be built using scavenged materials, either procured from a free source (i.e. freecycle), or found in trash bins or alleyways.

Presentation and Scoring: Teams will present their Machine through a creative skit of 5 - 10 minutes, as well as through a straightforward presentation to a panel of "dignified" judges, who will present the team with a subjective score on a scale of 1 - 5 in each of the following categories: Creativity, Artfulness, Resourcefulness, Objective, and Function.

Teams: Composed of 2 - 6 people of any age, and may meet whenever/wherever is convenient for them.

Meetings: There will be an initial informational meeting on Wednesday, February 20 at 5:30pm where the project will be announced and examples will be provided. You will be able to join a team, ask questions, or seek clarification on the project. There will be a subsequent session on Wednesday, March 6 at 7pm to ask questions, brainstorm, or develop your idea, otherwise teams are free to meet whenever and wherever is most convenient for them.

Presentation: Tuesday, May 14 at 7pm.

Winners: The winning team will receive a $100 gift certificate to Two Dollar Radio Headquarters, an HQ Supreme Membership, an annual subscription to Two Dollar Radio publications, and bragging rights until the end of time.

Questions to consider, that you may be asked, and that your machine should answer:

How does your machine disrupt or subvert public space?

Is it legal?

How does your machine fight “for the rights of a community, and for an alternative and sustainable existence?”

Is it social?

How does it exercise freedom?

Did you deploy the machine?

Where?

Was it neighborhood specific?

Registration: Sign up individually or register a team.

More on Co-Machines: Mobile Disruptive Architecture:

"In the midst of the pandemic, we are left to consider “Whose movement in public space is restricted, who inhabits the city now, what sorts of controls and regulations are being put into place to stop and make public action more illegal, and who would this serve? The Co-Machines are machines of crisis, and a means of responding to regulation policing public space.” –Dan Dorocic

"In the midst of the pandemic, we are left to consider “Whose movement in public space is restricted, who inhabits the city now, what sorts of controls and regulations are being put into place to stop and make public action more illegal, and who would this serve? The Co-Machines are machines of crisis, and a means of responding to regulation policing public space.” –Dan Dorocic

“Co-Machines are low-budget, often analogue, cheaply built, re-appropriating ready-mades such as shopping carts, bikes, and even irrigation systems, or incorporating very low-tech solutions. Yet they have to be clever in their design, sturdy, and easy to use and understand. They are in many ways the antithesis to the surveillance state, to the post-modern parametric surfaces and facades utilized by contemporary architects.” –Dan Dorocic

“…a barometer of how people act in public space with its limitations and potentials.” –Samuel Dias Carvalho

“The connective tissue draws on sociability, social-agency, and social-mindedness. These are works and ideas that bring people together, offer subjectivity for designer and audience alike, and operate in service of a larger common good.” –Mimi Zeiger

“How might a Co-Machine architecture, not at-risk laborers, Amazon drones, or fleets of autonomous robots, navigate the space of the social — that territory between the self and the boundaries of the state or private development?” –Mimi Zeiger

“While architecture can be civic and it can embody publicness or express a generosity to the street, it is principally procured and controlled by those with the most power.” –Nick Green

“They are experiments and excursions into the complex layers of the urban experience and while they are perhaps short-lived, they assert architecture in a different role, that of challenging the dominant power. For those who believe we all have a right to the city, we must consider what the responsibility of architecture is in enabling that right. Rather than thinking of architecture simply as a backdrop to everyday life or the structure inhabited by it, why not a direct-architecture that does not suggest, or hint at, communality, but which is enacted and utilized to generate something collective.” –Nick Green